Soybeans are among a group of plants that can essentially make their own nitrogen from air. A symbiotic relationship with bacteria enables this almost magical trait and scientists think it could be turned on in other plants, including corn and wheat.

For those not familiar with nitrogen “fixing,” it is the process of converting nitrogen (N2) in the air into a usable form for plants. Some plants, especially legumes like soybeans, have developed symbiotic relationships with bacteria that live within nodules on their root systems. These bacteria use energy from the plant to convert nitrogen gas from the air into ammonium (NH4), providing essential nutrients to the plant.

Researchers from Aarhus University in Denmark say they’ve identified a key mechanism involved in the nitrogen-fixing process. They identified two acids in a root protein that acts as a receptor. The receptor functions as a switch, enabling the plant to distinguish between “friend” and “foe” microorganisms in the soil.

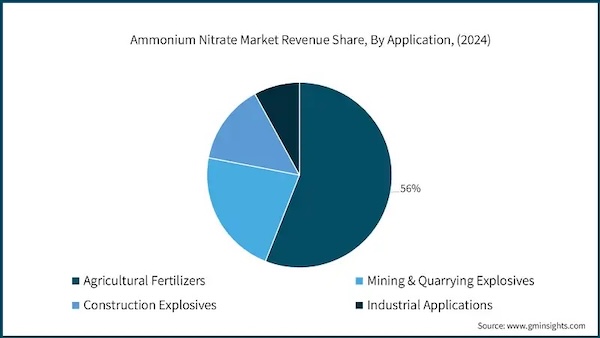

While most receptors trigger an immune defense to reject bacteria, the researchers found they could reprogram the receptor’s function by changing these two amino acids. This small modification transforms an immunity-triggering receptor into one that initiates symbiosis with bacteria that enable nitrogen fixation. In theory, this would make the plants self-sufficient in nitrogen and thus reduce the need for artificial fertilizer

To prove their theory, the team successfully performed the genetic modification on a model plant, “Lotus japonicus.” The same principle also worked in barley, proving that this major metabolic shift can be achieved with a remarkably small number of changes.

The researchers believe the ability could be turned on in many more crops. The trick is finding other essential keys that determine successful nitrogen fixation. Other factors governing root architecture, bacterial infection, and nodule formation also need to be explored and perhaps integrated into breeding or biotechnological programs. And of course, rigorous field testing will be essential to evaluate the true efficacy and long-term stability on modified plants.

This is just one avenue that scientists are exploring to stimulate the production of essential fertilizers in other crops. Scientists at UC Davis, for instance, recently announced a nitrogen-fixing wheat variety created with the gene-editing tool CRISPR. Other companies are working on developing biological solutions, such as Bayer, through a partnership with Ginkgo Bioworks that is pretty hush-hush. All that’s known is Ginkgo is developing microbes that will associate with crops and feed them nitrogen throughout their life cycle. (Sources: Technology Networks, ISAA, Bioengineer, C&EN)