The US Food and Drug Administration recently revealed some big changes coming in 2026. Among them is a significant shift in the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) substances guidelines. The changes would require companies to notify FDA and provide safety data before they are permitted to introduce a new food ingredient into the food supply. That’s in contrast to the current system in which companies can self-affirm an ingredient is “safe.” Below is more information about GRAS and how the proposed changes could impact food companies.

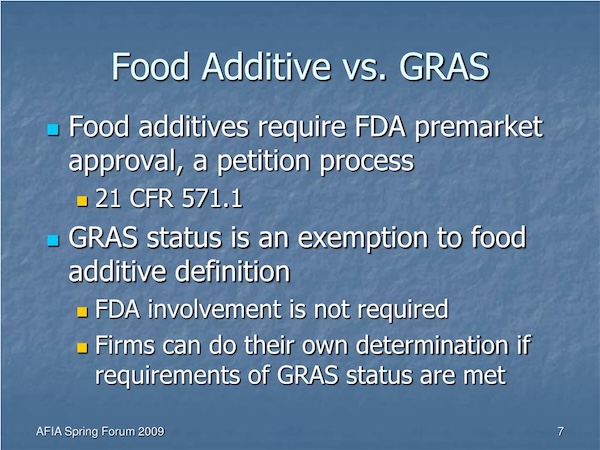

What is GRAS? GRAS is a regulatory category created in 1958 under the Food Additives Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in order to restore public trust in food safety while avoiding lengthy premarket reviews by the FDA for ingredients that are commonly used and widely accepted as safe. Some of these ingredients include salt, vinegar, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), and citric acid. According to sections 201(s) and 409 of the “Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act,” to qualify as GRAS an ingredient must be “generally recognized, among qualified experts, as having been adequately shown to be safe under the conditions of its intended use.”

Key Changes to GRAS: In 1970, the FDA launched a full-scale review of all presumed GRAS substances. This involved evaluating the scientific evidence supporting each substance’s safety and determining if it should retain GRAS status. The FDA then introduced a petition-based process, allowing manufacturers to seek confirmation of GRAS status. However, the process was highly time-consuming, taking up to 6 years (72 months) for the FDA to respond to a single petition. After more than a decade, FDA in 1982 admitted that its GRAS review process was unsustainable and stopped conducting active reviews but continued to respond to petitions on a case-by-case basis when submitted by manufacturers. By the 1990s, FDA recognized that the petition process was still too burdensome for its staff and budget resources and proposed in 1997 to replace it with a voluntary GRAS notification system. Under the notification procedure, companies self-determine GRAS status and may notify the FDA, which can either accept the notification or request further evidence. However, companies could still market substances as GRAS without notifying the FDA, provided they could demonstrate expert consensus on safety. This system has enabled a wide range of new food additives, from synthetic flavorings to novel proteins, to enter the U.S. food supply without premarket FDA approval or public disclosure — hence the GRAS “loophole.”

How Widely is GRAS Used: According to a 2022 report from the nonpartisan Environmental Working Group (EWG), nearly 99% of food chemicals introduced since 2000 have entered the market through the GRAS pathway. Currently, FDA maintains a GRAS notification program that includes a public inventory of GRAS notices. However, the program does not account for all food ingredients that enter the market through the self-affirmation process. Experts estimate more than 1,000 GRAS substances have entered the food supply without FDA or public knowledge. Notably, color additives are not classified under GRAS, as they are all subject to FDA approval.

Why GRAS is Controversial: Critics have raised concerns about the GRAS designation for food for years. Many view the GRAS process as a “loophole” that allows food additives to reach the market without appropriate safety reviews. Some also claim that letting companies to self-affirm the safety of ingredients has allowed dangerous chemicals with unknown health impacts to be unleashed into our food supply. Companies can also continue using substances they designate as GRAS, even when the FDA expresses concerns.

FDA Proposed Rule: The FDA in early September published its proposed changes to GRAS, which would require companies to submit mandatory notices whenever they want to use a substance they believe is GRAS. The proposed rule would exempt substances that are already listed or affirmed as GRAS, or ingredients where the FDA has issued a “no questions letter.” Additionally, it would require FDA to maintain and update a public-facing GRAS notice inventory for all GRAS substance notifications and their conditions of intended use. It would also spell out the process under which the agency would determine a substance to not be GRAS. The proposed rule is scheduled to be published in October. The Unified Agenda notice referencing the future proposed rule was posted in early September, which is available HERE.

Industry Concerns About GRAS Changes: The GRAS notification procedure requires that FDA respond to a GRAS notice within 180 days, with an option to extend the 180-day timeframe by 90 days on an as needed basis. However, insiders say that it can take more than two years to get a “no questions” letter from the FDA. Industry stakeholders worry that the new rules will dramatically increase approval times, particularly if the agency doesn’t receive increased funding and resources. Companies are also not keen on the additional red tape and expenses that will result from requiring a filing with the FDA.

Legal Questions: Many have already raised questions about the legality of the proposed GRAS changes. The FDA previously acknowledged that it does not have the express statutory authority to mandate GRAS notifications. However, when Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. first directed the FDA to explore the rule changes, he noted that HHS would work with Congress to create legislation if needed. Most legal experts think it’s a near-certainty that food companies will challenge the rule changes if they are published as written and without separate legislation from Congress. (Sources: FoodSafety, EWG, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP)