Meteorologists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have issued a La Niña watch, which could have significant impacts on weather across the globe this fall.

The La Niña weather pattern, as well as its counterpart El Niño, are the “cold” (La Niña) and “warm” (El Niño) phases of one of the most significant climate phenomenon on the planet, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Currently, it is in a neutral state but NOAA warns conditions could be setting up for a La Niña in the next six months, giving it a 50% to 55% chance of happening. That’s not a terribly strong probability but early warnings can help those that might be affected plan for challenging or even dangerous conditions. Below is more information about what La Niña is and how it could impact agriculture and other areas:

What Is La Niña: La Niña (“little girl” in Spanish), like El Niño (“little boy” in Spanish), is a weather pattern that can occur in the Pacific Ocean every few years. La Niña is characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific, compared to El Niño, which is characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific. In a normal year, winds along the equator push warm water westward. Warm water at the surface of the ocean blows from South America to Indonesia. As the warm water moves west, cold water from the deep rises up to the surface. This cold water ends up on the coast of South America. In the winter of a La Niña year, these winds are much stronger than usual. This makes the water in the Pacific Ocean near the equator a few degrees colder than it usually is. Even this small change in the ocean’s temperature can affect weather all over the world. La Niña events may last between one and three years, unlike El Niño, which usually lasts no more than a year. Both phenomena tend to peak during the Northern Hemisphere winter.

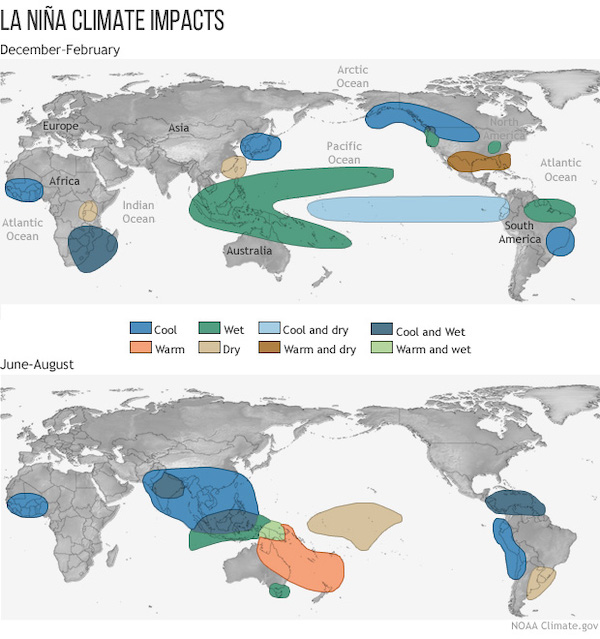

La Niña Impact on the Global Climate: Global climate La Niña impacts tend to be opposite those of El Niño impacts. In the continental U.S., during a La Niña year, winter temperatures are warmer than normal in the Southeast and cooler than normal in the Northwest. In South America, La Niña usually leads to increased rainfall in North Eastern Brazil, Colombia and other northern parts of South America and is associated with rainfall deficiency in Uruguay and parts of Argentina. La Niña has less of an effect in Europe but it does tend to lead to milder winters in Northern Europe (the United Kingdom especially) and colder winters in southern/western Europe.

U.S. Impact: In general, the stronger the La Niña, the more reliable the impacts on the United States. The typical U.S. impacts are warmer- and drier-than-average conditions across the southern tier of the United States, colder-than-average conditions across the north-central Plains, and wetter-than-average conditions in the Ohio Valley and Pacific Northwest/northern California. However, there is a great deal of variability even among strong La Niña events. And some impacts are more reliable than others.

Increased U.S. Drought Risks: In the U.S., the southern tier tends to be dry during La Niña episodes. Such an outcome could intensify and spread drought already afflicting New Mexico, Texas, southern Colorado, and other areas nearby. At the same time, it tends to bring increased outbreaks of particularly cold weather from Alaska through much of Canada, and into the U.S. northern tier. It tends to bring more storminess to the Pacific Northwest and parts of the U.S. Midwest. However, it can bring warmer and drier winters and smaller snowpacks in the Northwest. The so-called “snowpack drought” in 2015 was during a strong El Nino.

Increased Hurricane Activity: For those in hurricane territory, a La Niña weather pattern is definitely not good news. A greater number of hurricanes and tropical storms are typically generated during the Atlantic Hurricane season when La Niña is present. By contrast, hurricane activity tends to be lower during El Niño. Atlantic Hurricane season runs from June 1 – November 30 so hopefully, El Niño comes later rather than sooner.

Historical Events: La Niña was last observed in 2017-18. Argentina harvested its worst soybean crop in nine years in 2018, and Brazilian corn output also came in below initial expectations. U.S. HRW wheat yields were poor that year and dryness in that area carried into the corn and soybean growing season. In contrast, during a La Nina in 2016-17, crops in those same regions were largely unaffected. The major difference was timing – the cold anomalies of the 2016-17 La Nina occurred almost entirely in 2016, giving way to warmer ones by January. But in 2017-18, a much stronger cold anomaly held from November through March.

The 2010–12 La Niña event was one of the strongest on record. The Midwest, Southeastern, and Northeastern United States experienced an extremely wet 2011, leading to flooding across the Mississippi River, Missouri River, and the Ohio River. Texas fell into major drought with 2010–12 being some of the driest years ever for the state, starting the 2010–13 Southern U.S. and Mexico drought. 2011 was also one of the hottest years in Texas history. It also caused Australia to experience its wettest September on record in 2010, and its second-wettest year on record in 2010.