Paraguay doesn’t get a lot of attention as a major agricultural producer but their output is a lot higher than you might realize. The South American country has been a long-time and consistent global soybean producer that is often relied upon to fill production gaps in neighboring Argentina and Brazil. Below are more details about often overlooked Paraguay and how they fit into the global soybean marketplace.

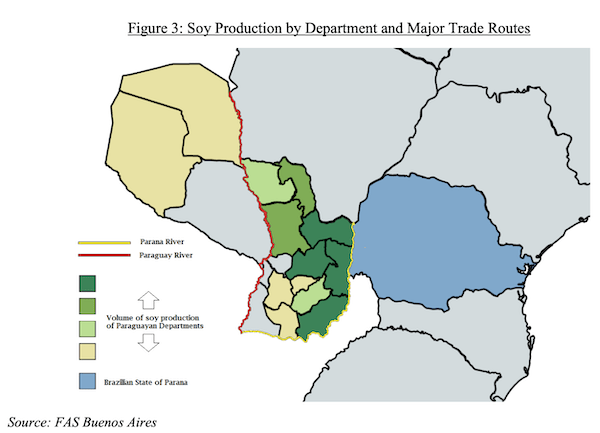

For those not familiar with Paraguay, the country is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to the east and northeast, and Bolivia to the northwest. Although one of only two landlocked countries in South America (Bolivia is the other), Paraguay has ports on the Paraguay and Paraná rivers that flow to the Atlantic Ocean, through the Paraná-Paraguay Waterway. The country is divided by the Río Paraguay into two well-differentiated geographic regions. The eastern region (Región Oriental); and the western region, officially called Western Paraguay (Región Occidental) and also known as the Chaco.

Soybeans are by far Paraguay’s biggest agricultural crop with production typically between 9 – 10 million metric tons (MMT) over the past decade. The major exception was marketing year 2021/22 when drought conditions severely impacted the crop and reduced output to just over 4 MMT. However, Paraguay’s soybean crop rebounded strongly in 2023/24. USDA estimates 2023/24 production at 10.5 MMT, though the local USDA Foreign Agricultural Service’s (FAS) post pegs the crop lower at 10.1 MMT. FAS also provides a 2024/25 soybean production forecast of 10.3 MMT on expectations of increased second-crop acreage. FAS in its most recent update noted that the return of La Niña this year could impact Paraguay’s soybean yields as the weather pattern generally results in drier conditions for the country.

Paraguay has an interesting soybean crop cycle. The country generally harvests two soy crops every year. The first crop, known as “zafra,” is the primary soy crop while second crop soybeans, or “zafriña” crop generally features fewer acres and lower yields. Producers plant soy followed by corn or vice versa. According to USDA, it is still common for Paraguayan producers to plant back-to-back soybeans but the practice is beginning to change with advisors pushing rotations with corn, wheat, or oats. The zafra crop is planted between the end of August and the first half of November and harvested between the end of December and late-March. The zafriña crop gets planted in January/February and harvested between late May and the end of July.

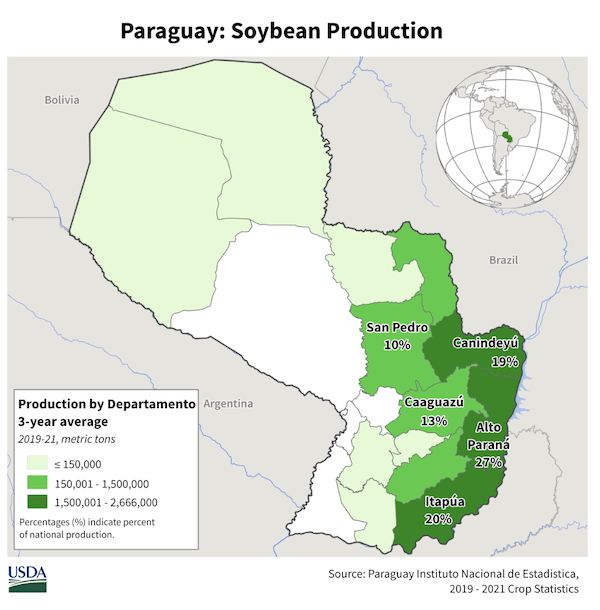

FAS notes that while the zafriña crop will get slightly more acreage this year, additional new soybean acres are unlikely going forward. There has been some talk of expanding soybeans in the western Chaco region but FAS says most experts in the country believe Paraguay’s crop production area has nearly reached its peak. FAS says additional growth in the main growing areas of the northern and eastern sections of the country is unlikely with the only potential being on marginal land, most of which has already been tapped.

While drought conditions eased in Paraguay last year, that was not the case in nearby Argentina, which is among the world’s most important soy crushers. Around 80% of Paraguay’s 23/24 production was exported to Argentina to help meet crush demand. In January-February of this year, Paraguay’s soybean exports rose by +238% with nearly all of it going to Argentina. FAS expects soybean exports in 24/25 will return to more typical levels as Argentina’s new crop soybean harvest becomes available.

Paraguay doesn’t consume much of its soybean or crush production domestically. A large share of whole beans get exported to Argentina, even in non-drought years. It’s generally more profitable for companies to export to Argentina and to crush there than process soybeans in Paraguay, according to FAS, and many large companies have plants in both countries.

Paraguay’s total crush capacity is currently estimated at 5.04 MMT though FAS says that could increase up to 5.79 MMT once a new crushing facility in the western Chaco region becomes operational. That’s expected to happen in earnest sometime in 2025. FAS says this could result in an operational crush rate of 60% next year. FAS says crushers reported using less than 30% of their capacity in January 2024.

In 2023/24, with Argentina heavily dependent on imports, Paraguay’s crush this year is estimated at just 2.98 MMT by FAS. That’s quite a bit lower than USDA’s official forecast of 3.5 MMT and down from around 3.45 MMT in 22/23. With fewer whole soybeans expected to go to Argentina in 24/25, FAS expects crush to rebound back toward the 3.5 MMT level.

Paraguay also has little domestic demand for soymeal and soy oil, consuming only a small fraction of production. FAS forecasts exports of soy meal and oil to increase in line with additional crush in 2024/25 after lower crush and exports in 2023/24. FAS expects the bulk of soymeal exports to return to more traditional trading partners beyond Argentina in MY 2024/25 such as the E.U., Chile, and the United Kingdom as Argentina’s harvest and crush right size following the years of drought.

Likewise, the bulk of Paraguay’s soy oil goes to exports, which are expected to rebound to normal levels in 2024/25. FAS notes that domestic demand for soy oil could increase in coming years if a planned biodiesel plant becomes operational. The Omega Green facility was slated to be operational this year but FAS says the project is still ongoing and seems unlikely to be online in 2025 either. The full FAS report is available HERE.