Heading into planting season, there is a lot of talk about a lack of moisture in some key growing regions. Much of the US Midwest experienced a warmer-than-usual winter which, in addition to drying out soils, could cause other issues for producers this year.

This year’s warmer-than-typical winter is mostly blamed on the El Niño weather pattern that developed last year. According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), every month since June 2023 has set a new monthly global temperature record.

Looking at the US Drought Monitor, there are surprisingly few patches of drought across the country thanks to some big precipitation events. In fact, extreme and excessive drought that has long been in place across the south and west has nearly been eliminated, as well as some of the short-term moisture deficits in the Plains.

Agricultural areas in drought still include about 32% of the US corn-growing region and 31% of soybeans. That compares to 40% and 32%, respectively, at this same time last year, so on the surface, things appear to be in much better shape.

Diving a little deeper, there is a troubling amount of drought still over Iowa, the top production state for corn and the second biggest soybean producer. As of February 20, the US Drought Monitor placed 79% of the state’s corn area in some form of drought. Specifically, 23% of the state’s corn is in “extreme drought,” while 36% is in “severe drought,” and 20% in “moderate drought.” Additionally, 78% of Iowa’s soybean area is in drought, with 20% considered “extreme,” 35% “severe,” and 23% “moderate.”

In Nebraska, the number three corn producer and a top-five soybean producer, drought is impacting about half the states corn area, including 27% in “severe drought.” Meanwhile, over 60% of the soybean area is in some form of drought with 29% considered “severe drought.”

It’s way too early to start panicking about the lack of moisture in big production states just yet but the situation will continue to be closely monitored. Right now, producers are hoping spring rains will make up most of the shortfalls.

A longer-term impact from this year’s warm winter is insect pressure. Many agricultural pests can thrive in overly warm winters, especially if it never gets cold enough for the ground to freeze. Due to a lack of cold in Iowa, for instance, this year’s maximum frost depth at Des Moines peaked at one of the lowest levels in recent history, and had no frozen ground by early February, something that has not happened in recent history according to local meteorologists.

Interestingly, warmer weather doesn’t necessarily guarantee that insect pressure will be greater in any given year. According to Erin Hodgson, assistant professor of entomology at Iowa State, warm winter days could cause insects to become active (e.g., woolly bear caterpillars) when they normally would be dormant. Activity uses up stored fats they depend on to survive until the spring. Without access to food, these active insects could starve to death before food becomes available. Bottom line, predicting pest pressure is very difficult but it could be a year where vigilant scouting and early mitigation efforts pay off more than usual.

Similar to insects, warm winters can also lead to increased crop disease pressures. When temperatures during the winter months are not consistently low, even pathogens like the rust fungi that do not usually survive Midwest winters are able to overwinter on volunteer plants and in cultivated fields. Even diseases that do typically survive harsh winter temps can be supercharged by a mild winter. For instance, polycyclic diseases like rust and powdery mildew may be able to get an early start, producing several batches of spores before grain-fill is even reached. Early disease typically equates to more disease and greater yield loss, especially if not optimally managed.

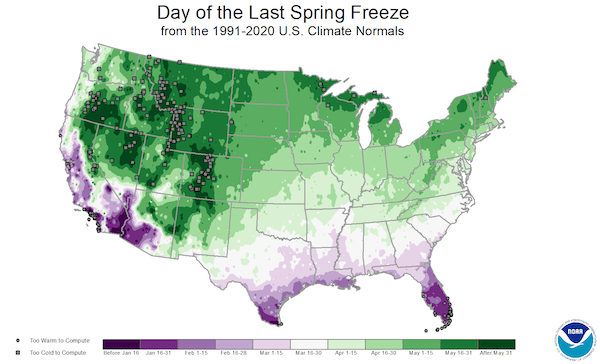

Of course the other major risk to crops is that they end up getting planted too early by farmers chomping at the bit to get back into the field. We’ve heard from guys already getting started in Alabama, Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. It’s obviously a riskier proposition for some of the more northern states where the last spring frost dates stretch well into April. (Sources: USDA, NOAA, Iowa State, DTN)