The El Niño weather event that was officially declared last year is believed to be nearing its peak, according to the latest outlook from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). While El Niño conditions will stick around for another few months, the impacts to global weather patterns will continue to lessen as El Niño weakens and ENSO-neutral conditions return. Now, some climate models are predicting that the ENSO pattern could flip back to La Niña by late summer, which could have big implications for 2024/25 crop production.

For those not familiar, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle. El Niño events are characterized by warmer-than-normal seas in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. By contrast, La Niña marks a cooling of the ocean surface, or below-average sea surface temperatures, in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral, when neither El Niño or La Niña is present.

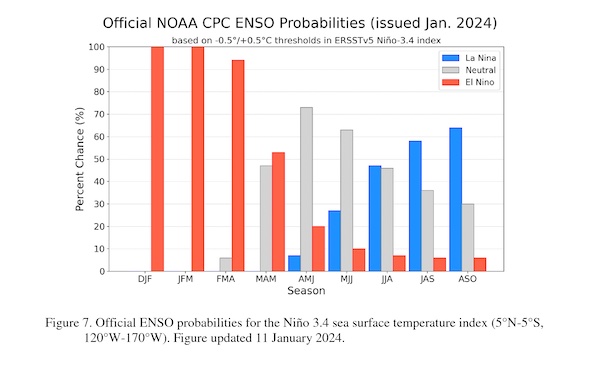

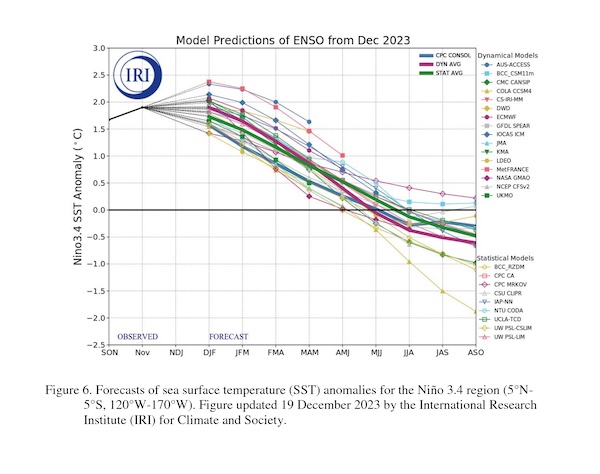

There is a 73% chance that El Niño will end in the April to June period, according to the NOAA’s latest forecast. The latest model suggests El Niño will gradually weaken and transition to ENSO-neutral conditions this spring. NOAA notes that while some climate models suggest a transition to ENSO-neutral as soon as March-May 2024, its forecasters still think the April-June timeframe is more likely.

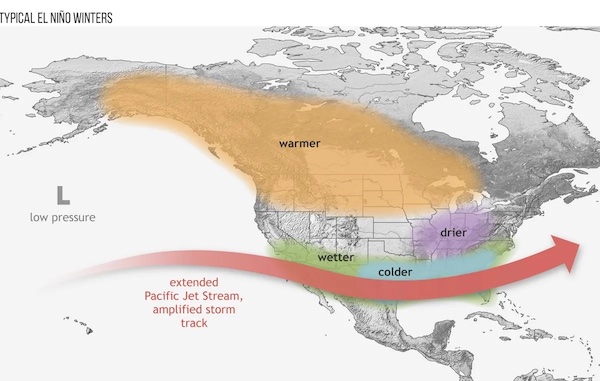

NOAA says that the average El Niño lasts nine to 12 months and it is typical for the event to peak in December/early January. A strong El Niño winter usually means a colder, wetter winter for California and the Southern U.S, but a warm, dry winter for the Pacific Northwest and Ohio Valley. That’s in line with how winter has played out so far this year and what’s expected to continue for the next several months.

It’s worth noting that the second year of El Niño tends to be warmer than the first, meaning 2024 could be even hotter than 2023, which was a record breaker. According to Bloomberg, every month in 2023 was warmer than the 1991-2020 average, and the latter part of the year, after El Niño started, shattered records: June, July, August, September, October, November and December were all the hottest of their respective months in recorded history. July was the warmest month ever observed.

NOAA also says there are increasing odds of La Niña in the seasons following a shift to ENSO-neutral. If you recall, the world experienced three seasons in a row of La Niña that ran from the Northern Hemisphere winter of 2020-2021 through the 20222-23 winter season. A return of La Niña this summer could mean higher chances of drought in the southern U.S. and heavy rains and flooding in the Pacific Northwest and Canada.

One big worry is the ongoing drought conditions over some key growing regions. According to DTN meteorologist John Baranack, “2023 ended with a large area of drought in the middle of the country, especially around Iowa and eastern Nebraska as well as the Lower Mississippi and Tennessee river valleys.” While El Niño has encouraged more moisture in these regions so far this winter, drought conditions remain. Keep in mind, deepening drought could also spell more transportation problems along the Mississippi River, which dropped to historic low levels for the second year in a row in 2023.

Obviously, a slew of other factors impact weather patterns and it’s impossible to predict conditions this far out. But it’s worth bracing for what could be an especially wild weather year in 2024! (Sources: NOAA, DTN, Bloomberg)