Women that woke up in America on this day 102 years ago did not know if they would be allowed to vote in the upcoming presidential election. Laws in some states prevented married women from owning property or even having a legal claim to money that they earned. With no legal right to the vote, American women had no way of influencing those laws. But everything would change before sunset on this day, August 18, 1920, thanks to over 70 years of tireless suffrage efforts and a good son from Tennessee whose mother convinced him to vote in favor of the 19th Amendment.

The first formal national women’s rights group formed in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Convention, which made the demand for the vote a centerpiece of the movement. In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) with their eyes on a federal constitutional amendment that would grant women the right to vote. NWSA morphed into the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890.

As the NAWSA worked toward guaranteeing women the vote at the federal level, progress was being made in some states. Between 1910 and 1918, over 15 states had already given women the right to vote. Facing tough reelection in 1918, President Woodrow Wilson changed his stance on the issue and played to public support for it in those states and others. He fully backed the proposed suffrage amendment, tying it to WWI and the critical roles women had played in the war effort. It fell two votes short of passage on the first try in 1918 but Congress eventually passed the amendment in June of 1919, sending it to the states for ratification.

By the summer of 1920, 35 of the required 36 states had ratified the 19th Amendment that stated, “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Tennessee became the pivotal battleground when the amendment made it to the state House on August 18, 1920. The 96 all-male lawmakers are said to have been evenly divided with half wearing yellow rose lapel pins, signaling support for suffrage, while the other half broadcast their opposition with a red rose.

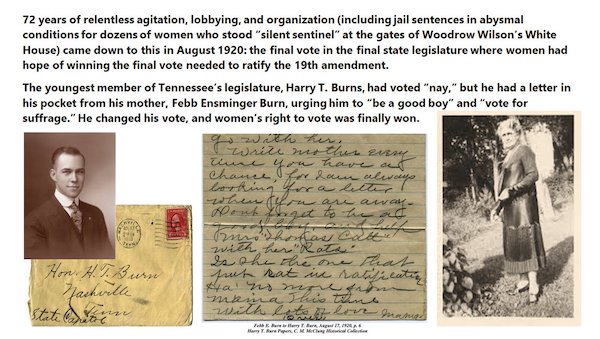

The legislature’s youngest member, 24-year-old Harry T. Burn, wore a red rose lapel pin and had twice voted unsuccessfully to table the measure. That was despite a letter from his mother, Febb Burn, which said, “Hurrah, and vote for suffrage! Don’t keep them in doubt. I notice some of the speeches against. They were bitter. I have been watching to see how you stood, but have not noticed anything yet.” She was referring to speeches delivered by anti-suffragists in the lead up to the vote, most of which were blatantly sexist and racist. When the actual vote came around, clutching his mother’s letter, he shocked everyone with an “aye.” That single vote passed the Nineteenth Amendment, enfranchising 26 million American women in time for the November 2, 1920, U.S. presidential election, which Wilson won.

Harry’s move was a big gamble – he was also facing reelection and in a district that strongly opposed suffrage. His constituents actually passed a resolution demanding he vote “no.” After his defiant vote in the House, he was immediately accused of bribery and wrongdoing. The wife of a former Louisiana governor showed up at his mother’s house to lecture her for four hours, trying to persuade her to change her son’s mind. The day after the vote, Harry read this speech on the House floor: “I believe in full suffrage as a right. I believe we had a legal and moral right to ratify; I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

Febb later told the Nashville Tennessean, “I am glad that he loved me enough to say afterward that my letter had so much influence on him. I am proud of my son. He has covered himself with glory.” Harry won that reelection bid and many others, going on to various public offices until he retired in the 1970s.

I should note, Harry Burn was born in Mouse Creek, Tennessee to James Lafayette Burn and Febb Ensminger Burn. His father was the stationmaster at the local depot and passed away somewhat early. His mother worked as a teacher after her graduation from U.S. Grant Memorial University (now Tennessee Wesleyan University) and she later ran the family farm. Chalk up another victory to the women leaders in rural America! (Sources: History, Nashville Tennessean, Center for American Progress)