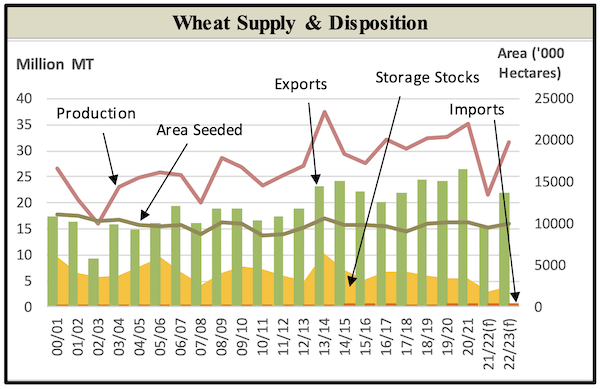

After weather and war dealt a disastrous blow to this year’s global wheat supplies, there is a great deal of hope now pinned on traditional suppliers to maximize production in the 2022/23 season. There are a lot of eyes on Canada’s wheat right now where the country’s grain production is expected to rebound from last year’s drought-induced losses. That’s of course dependent on the weather cooperating this year, which is so far proving to be a mixed bag.

The USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service attaché in Ottawa said in its recent update that dry conditions persist in Alberta and Western Saskatchewan and many farmers are behind in their planting schedule, due to unfavorable planting conditions. The FAS post notes that planting is running a week or two behind due to cold temperatures and/or precipitation in the prairies, and excess moisture in Ontario and Quebec.

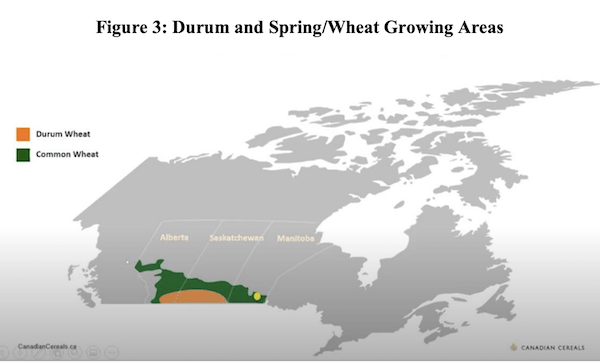

During the 2021/22 season, production of wheat, corn, barley, and oats fell nearly -30%, mainly due to the negative impact of the prairie drought on cereal yields. Spring wheat production fell -38% in 21/22 to 16 million metric tons (MT), largely the result of a -9% reduction in area planted and lower yields. Spring wheat is the most commonly grown variety in Canada, representing 75% of wheat produced over the past five years. Durum wheat production was even more disastrous, falling -60% to just 2.7 million MT, despite a slight increase in planted area. Durum wheat is historically the second most common wheat variety grown in Canada.

In contrast, winter wheat production increased +8% to 3 million MT, thanks to record yields. That also resulted in winter wheat production exceeding durum production for the first time in at least 22 years. Winter wheat is primarily grown in Ontario, where soil moisture levels were, and continue to be superior to the spring wheat and durum growing areas of the prairies, according to FAS.

Production of wheat in 22/23 is seen rebounding partially on a projected increase in planted area to both spring and durum wheat. FAS notes that planting decisions will ultimately be guided by canola disease pressures, dry planting conditions, high input prices, and high wheat prices, all of which favor increased wheat planting relative to alternative crops such as canola.

FAS says some evidence suggests planted area growth could be muted despite currently higher prices. Most farmers that have long-term rotation plans will probably stick with those. Additionally, though wheat is a low input crop relative to canola and corn, many farmers purchased their inputs months ago, before the fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent fertilizer prices higher. Therefore, the high input prices of wheat alternatives are not necessarily a deterrent.

Countries such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, Morocco, and Tunisia typically depend on both Ukraine and Canada (and other countries) for their wheat supplies. From Canada, these countries import Canadian Western Red Spring (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Morocco) and Canadian durum (Indonesia, Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia), while they import primarily winter wheat from Ukraine. FAS says Canada’s winter wheat is most commonly sold in the Americas, but strong demand for mid-/low-protein wheat in the Middle East, North Africa, Sub Saharan Africa, and South Africa may lead to diversification of winter wheat exports to these regions in MY 2022/23.

FAS also says industry contacts foresee Canada becoming a market of last resort for price-conscious countries that tend to blend Canada’s high-protein wheat with lower-protein, lower-cost wheat, such as Ukrainian winter wheat. Consumers in price-conscious wheat-importing countries may substitute out products that use high-protein wheat blends, or substitute out wheat products altogether for other carbohydrates, such as rice. The full report is available HERE.