Betty Crocker might be one of the most trusted names in American kitchens. For nearly 75 years, cooks have consulted the red and white cookbooks bearing her name to answer all their basic culinary questions. Before that, home cooks tuned into her radio and then television shows seeking solutions to their kitchen dilemmas. Her name is on the country’s most popular baking mixes and canned frosting. But who exactly was this woman in which American cooks have placed so much faith?

Believe it or not, Betty Crocker was a fictitious character developed, somewhat out of desperation, by an overwhelmed advertising department manager. Washburn-Crosby, a flour milling company that eventually became General Mills, owned the brand Gold Medal Flour. In 1921, an ad for the flour was placed in the Saturday Evening Post. It featured a puzzle that readers were encouraged to solve and then send to Gold Medal for a chance to win a sack of flour.

Washburn-Crosby at the time directed all its customer mail to its very small, all-male advertising department. The men usually consulted women in other departments for the answers to customer cooking and homemaking questions. The story is that department manager Samuel Gale never felt comfortable signing his unmistakably male name to responses, as he thought women homemakers wanted to hear from a female authority. When the department was overwhelmed with some 30,000 completed puzzles from their ad campaign, most of which had attached cooking questions, they invented Betty Crocker as their de facto signatory.

“Crocker” was chosen to honor the recently retired director of Washburn-Crosby, William G. Crocker. “Betty” was chosen because it was familiar and sounded wholesome. Samuel Gale asked the female employees of Washburn-Crosby to submit samples for the personal signature. The winner was penned by a secretary named Florence Lindeberg. Her Betty Crocker signature was used in response to all letters regarding baking, cooking, and domestic advice. Eventually, Betty became so popular that other employees had to be trained to reproduce her increasingly recognizable signature.

In 1924, Washburn-Crosby launched their breakout star on a radio show, the “Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air” on Minneapolis radio station WCCO, which Washburn-Crosby also owned. It was the country’s first radio cooking program and proved so popular that it was soon airing nationwide. The first voice of Betty Crocker belonged to two home economists named Blanche Ingersoll and Marjorie Child Husted. It was Husted who also wrote the scripts, as well as led a team of home economists to create and triple-test recipes.

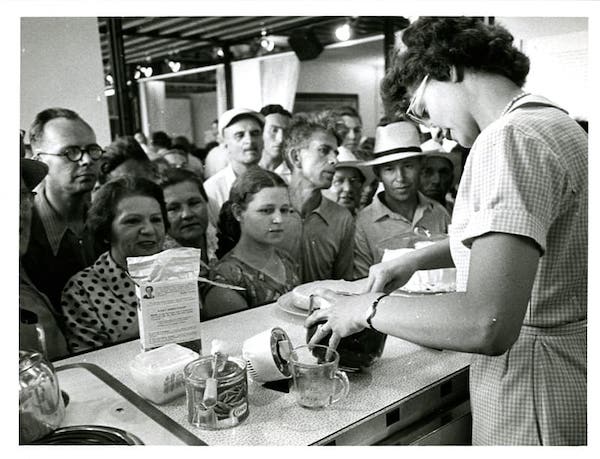

The name was given a live human face in 1949 when actress Adelaide Hawley Cumming became Betty Crocker. She appeared for several years on The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show, and later the “Betty Crocker Star Matinee.” The face of Betty Crocker in print ads and on product labels has been depicted by various artists since the 1920s. In 1936, Neysa McMein created the first official portrait of Betty, a composite painting that blended the facial features of the female staff in Washburn-Crosby’s home service department. Since 1955, Betty’s image has been updated seven times, though she has remained a perpetual 30-35 years old.

Betty Crocker’s first namesake grocery item was a soup mix, which became available in 1941. Her famous cake mix appeared on store shelves in 1947. Starting in 1930, General Mills issued softbound recipe books but it wasn’t until 1950 that it published the bestselling “Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book,” known affectionately as “Big Red.” More than 75 million copies of the book have been sold since.

Fortune magazine told America the truth about Betty in 1945, the same year it also named her the second-most popular woman in America, right after Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1981, Berkeley Breathed imagined Betty Crocker as a real person. In his daily comic strip, Bloom County, Milo Bloom goes on a quest to find America, which to him means finding Betty Crocker herself. And that seems to be exactly what General Mills was going for when it created the unlikely cultural icon that has helped seven generations of Americans feed their families. (Sources: PBS, Smithsonian Magazine, Epicurious)