I was sent this interesting article the other day and I wanted to pass it on and share. I did some research and the text was simplified from the article and deep research report titled, “The Homestead Act of 1862” by Lee Ann Potter and Wynell Schamel. I think we should all spend some time and think about how thankful we have to be for those family members that came before us and did some serious heavy lifting. Let’s also remind ourselves that our farming families have also received a lot of help and support from our government through the years.

On January 1, 1863, Daniel Freeman, a Union Army scout, was scheduled to leave Gage County, Nebraska Territory, to report for duty in St. Louis. At a New Year’s Eve party the night before, Freeman met some local Land Office officials and convinced a clerk to open the office shortly after midnight in order to file a land claim. In doing so, Freeman became one of the first to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the Homestead Act, a law signed by President Abraham Lincoln in May of 1862. At the time of the signing, 11 states had left the Union, and this piece of legislation would continue to have regional and political overtones.

The distribution of Government lands had been an issue since the Revolutionary War. At the time of the Articles of Confederation, the major controversy related to land measurement and pricing. Early methods for allocating unsettled land outside the original 13 colonies were arbitrary and chaotic. Boundaries were established by stepping off plots from geographical landmarks. As a result, overlapping claims and border disputes were common.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 finally implemented a standardized system of Federal land surveys that eased boundary conflicts. Using astronomical starting points, territory was divided into a 6-mile square called a township prior to settlement. The township was divided into 36 sections, each measuring 1 square mile or 640 acres each. Sale of public land was viewed as a means to generate revenue for the Government rather than as a way to encourage settlement. Initially, an individual was required to purchase a full section of land at the cost of $1 per acre for 640 acres. The investment needed to purchase these large plots and the massive amount of physical labor required to clear the land for agriculture were often insurmountable obstacles.

By 1800, the minimum lot was halved to 320 acres, and settlers were allowed to pay in 4 installments, but prices remained fixed at $1.25 an acre until 1854. That year, federal legislation was enacted establishing a graduated scale that adjusted land prices to reflect the desirability of the lot. Lots that had been on the market for 30 years, for example, were reduced to 12 ½ cents per acre. Soon after, extraordinary bonuses were extended to veterans and those interested in settling the Oregon Territory, making homesteading a viable option for some. But basically, national public-land-use policy made land ownership financially unattainable for most would-be homesteaders.

In the 1830s and 1840s, rising prices for corn, wheat, and cotton enabled large, well-financed farms, particularly the plantations of the South, to force out smaller ventures. Displaced farmers then looked westward to unforested country that offered more affordable development.

Prior to the war with Mexico (1846–48), people settling in the West demanded “preemption,” an individual’s right to settle land first and pay later (essentially an early form of credit). Eastern economic interests opposed this policy as it was feared that the cheap labor base for the factories would be drained. After the war with Mexico, a number of developments supported the growth of the homestead movement. Economic prosperity drew unprecedented numbers of immigrants to America, many of whom also looked westward for a new life. New canals and roadways reduced western dependence on the harbor in New Orleans, and England’s repeal of its corn laws opened new markets to American agriculture.

Despite these developments, legislative efforts to improve homesteading laws faced opposition on multiple fronts. As mentioned above, Northern factories owners feared a mass departure of their cheap labor force and Southern states worried that rapid settlement of western territories would give rise to new states populated by small farmers opposed to slavery and also bring on more competition. Preemption became national policy in spite of these sectional concerns, but supporting legislation was stymied. Three times—in 1852, 1854, and 1859—the House of Representatives passed homestead legislation, but on each occasion, the Senate defeated the measure. In 1860, a homestead bill providing Federal land grants to western settlers was passed by Congress only to be vetoed by President Buchanan.

The Civil War removed the slavery issue because the Southern states had seceded from the Union. So finally, in 1862, the Homestead Act was passed and signed into law. The new law established a three-fold homestead acquisition process: file an application, improve the land, and file for deed of title.

Any U.S. citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. Government could file an application and lay claim to 160 acres of surveyed Government land. For the next 5 years, the General Land Office looked for a good faith effort by the homesteaders. This meant that the homestead was their primary residence and that they made improvements upon the land. After 5 years, the homesteader could file for his patent (or deed of title) by submitting proof of residency and the required improvements to a local land office.

Local land offices forwarded the paperwork to the General Land Office in Washington, DC, along with a final certificate of eligibility. The case file was examined, and valid claims were granted patent to the land free and clear, except for a small registration fee. Title could also be acquired after a 6-month residency and trivial improvements provided the claimant paid the government $1.25 per acre. After the Civil War, Union soldiers could deduct the time they served from the residency requirements.

Some land speculators took advantage of legislative loopholes. Others hired phony claimants or bought abandoned land. The General Land Office was underfunded and unable to hire a sufficient number investigators for its widely scattered local offices. As a result, overworked and underpaid investigators were often susceptible to bribery.

Physical conditions on the frontier presented even greater challenges. Wind, blizzards, and plagues of insects threatened crops. Open plains meant few trees for building, forcing many to build homes out of sod. Limited fuel and water supplies could turn simple cooking and heating chores into difficult trials. Ironically, even the smaller size of sections took its own toll. While 160 acres may have been sufficient for an eastern farmer, it was simply not enough to sustain agriculture on the dry plains, and scarce natural vegetation made raising livestock on the prairie difficult. As a result, in many areas, the original homesteader did not stay on the land long enough to fulfill the claim.

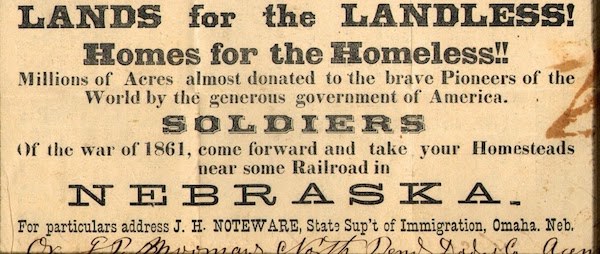

Homesteaders who persevered were rewarded with opportunities as rapid changes in transportation eased some of the hardships. Six months after the Homestead Act was passed, the Railroad Act was signed, and by May 1869, a transcontinental railroad stretched across the frontier. The new railroads provided relatively easy transportation for homesteaders, and new immigrants were lured westward by railroad companies eager to sell off excess land at inflated prices. The new rail lines provided ready access to manufactured goods and catalog houses like Montgomery Ward offered farm tools, barbed wire, linens, weapons, and even houses delivered via the rails.

On January 1, 1863, Daniel Freeman and 417 others had filed claims. Many more pioneers followed, populating the land, building towns and schools and creating new states from the territories. In many cases, the schools became the focal point for community life, serving as churches, polling places and social gathering locations.

In 1936, the Department of the Interior recognized Daniel Freeman as the first claimant and established the Homestead National Monument, near a school built in 1872, on his homestead near Beatrice, Nebraska. Today, the monument is administered by the National Park Service, and the site commemorates the changes to the land and the nation brought about by the Homestead Act of 1862.

By 1934, over 1.6 million homestead applications were processed and more than 270 million acres—10 percent of all U.S. land—passed into the hands of individuals.