I’m always fielding questions from producers and investors in different parts of the country that are curious about the various classes of wheat. We put together a quick little cheat sheet that should help simplify and more easily explain.

Wheat was first brought to the U.S. by early colonists from Europe who had become accustomed to the superior baked goods it produced. Today, it is the third-largest U.S. field crop behind corn and soybeans, though both acreage and production have fallen dramatically since peaking in the 1980s. Still, it is the principal food grain produced in the U.S., used in everything from bread and noodles to beer and breakfast cereal.

Wheat is a little more complicated than corn and soybeans, with two distinct growing seasons – spring and winter. Spring wheat classes are planted in the spring and harvested in the summer. Winter wheat hard is planted in the fall, grows several inches, and may even be grazed by livestock before the grain head develops. Winter wheat lies dormant through the winter, continues growing in the spring, and is harvested in the summer months. These break down further into six main classes that have unique qualities sought by millers and food processors for specific products. Below is more information about the different classes of wheat:

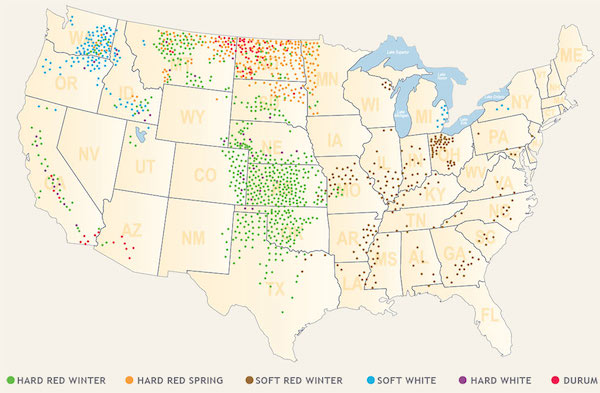

Hard Red Winter Wheat (HRW) is the most common variation of wheat grown in the U.S., counting for about 40% of total U.S. production and around half of exports. It is grown primarily in the Great Plains (northern Texas through Montana). HRW is extremely versatile with medium-to-high protein content of about 10-14% and mellow gluten content.

Hard Red Spring (HRS) wheat accounts for about 20% of production and is grown primarily in the Northern Plains (North Dakota, Montana, Minnesota, and South Dakota). HRS wheat is valued for its high protein levels of about 12.0 to 15.0 percent, strong gluten, and high water absorption. It’s a preferred ingredient for specialty breads as well as blending with lower protein wheat.

Soft Red Winter (SRW) wheat accounts for 15-20% of U.S. production and is grown primarily in States along the Mississippi River and in eastern States. Flour produced from milling-grade SRW has excellent baking qualities, making it a top choice for cookies, cakes and other pastries.

White wheat (both winter and spring) accounts for 10-15% of total production and is grown in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Michigan, and New York. Soft white wheat (SW) is used much the same way as soft red wheat for pastries rather than breads. It has a low protein, about 8.5 to 10.5%, and low water absorption. Hard white wheat (HW) is the newest class of wheat to be grown in the United States. It’s closely related to red wheats in its’ milling and baking qualities, however, it has a milder, sweeter flavor. Hard white wheat has a medium to high protein content, about 10 to 14 percent.

Durum wheat accounts for 3-5 percent of total production and is grown primarily in North Dakota and Montana. Durum, from the Latin word for hard, is the hardest of all wheat classes with amber-colored kernels larger than those of other wheat classes. Durum has a high protein content about 12.0 to 15.0 percent and is used most widely in pasta products. When the durum is milled, the endosperm is ground into a granular product called semolina which is also used to make pasta, as well as couscous.

Hard VS Soft – In general, the hard wheat classes (spring and winter) contain higher quantities of the proteins needed to produce bread, buns, pasta (durum), pizza crust, and other bread products. Soft wheat contains lower quantities of protein than hard wheat, and it is conducive to producing tender cookies, cakes, pastries, crackers, Asian noodles, and steam breads.

Red VS White – The white wheat classes are desirable because they lack a red gene in the bran that contributes to a darker color and a slightly bitter flavor to the whole grain. (Sources: USDA, Natural History of Wheat, Kansas Wheat)