USDA recently published a study analyzing the impact of absent farm landlords on the long-term economic and agricultural health for the 25 most important farm States by cash receipts. Interestingly, the study finds a greater prevalence of absent landlords is associated with lower rental rates and land values at the State level, but there appears to be no correlation with changes in rents and land values.

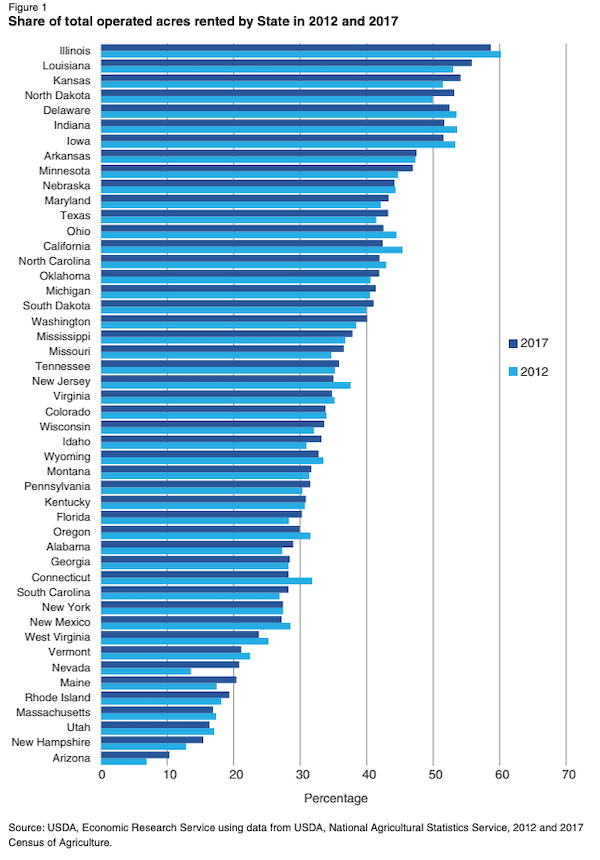

The study, directed by Congress in the 2018 Farm Bill, analyzed data from the 2014 USDA National Agricultural Statistics Survey’s Tenure, Ownership and Transition of Agricultural Land (TOTAL) report to develop one of the few studies using the actual distance of nonoperating landlords (NOLs) relative to the location of their farmland. Landlords are considered absent landlords if they don’t operate a farm and are located 100 miles or more from the farmland they rent to a farming operation. The TOTAL report showed approximately 39% of land in farms in the 48 contiguous states was rented as of 2014, or approximately 355 million acres. In some states, rented acres account for more than half of operated acres. Some of the rented farmland is owned by farmers who, in addition to farming their own farming operations, rent out land to other farmers. However, the TOTAL survey indicates that the majority of rented land (80 percent) was owned and rented out by landlords who do not operate farms. The full report is available HERE. Below are some of the highlights:

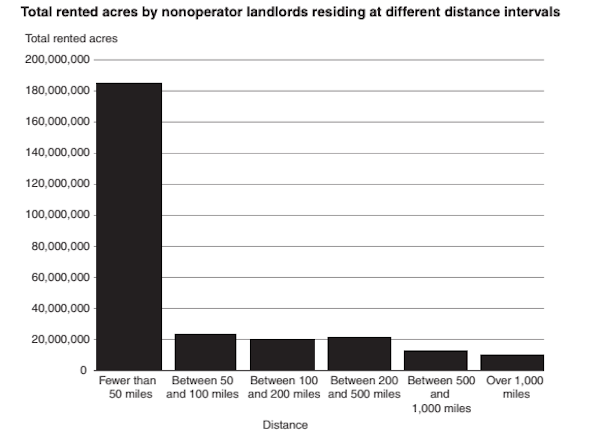

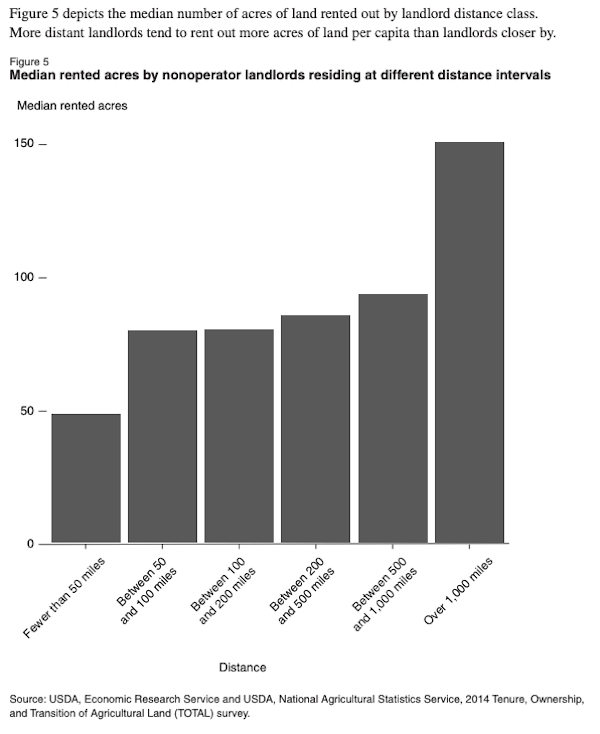

How far do NOLs live from their land? Distances between NOLs and their tenants vary considerably across States and regions but the majority in 2014 resided within 100 miles of the parcels they rented. A total of 185 million acres are owned by NOLs who live within 50 miles of their rented land (67 percent of all acres rented out by NOLs). The next landlord grouping, those living between 50 and 100 miles away, rent out a little more than 24 million acres. Total rented acres progressively decline as the distance between landlords and tenants increases, and the last group — those living more than 1,000 miles away — provides nearly 11 million acres, or almost 4 percent of the total acres rented out by NOLs. More distant landlords tend to rent out more acres of land per capita than landlords closer by. The Midwest differed from the rest of the United States in that the distances between landlords and tenants were, on average, significantly shorter than distances between landlords and tenants on the east and west coasts.

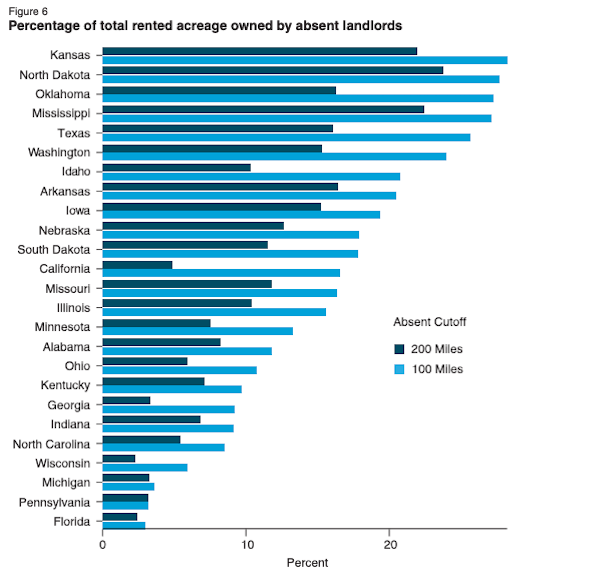

How prevalent are absent landlords? The study uses two classifications of absent landlords – those that reside more than 100 miles from their rented farmland and those that reside more than 200 miles from it. When using the 100-mile cutoff, absent landlords own nearly 20 percent of the acres rented in eight States. The prevalence of absent landlords was consistently higher in counties and States with lower rents and land values and weaker indicators of local economic development.

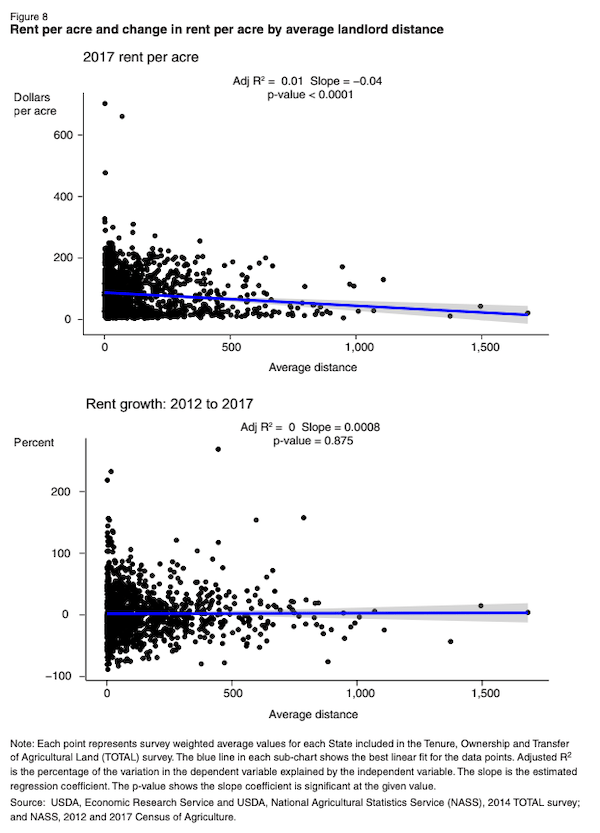

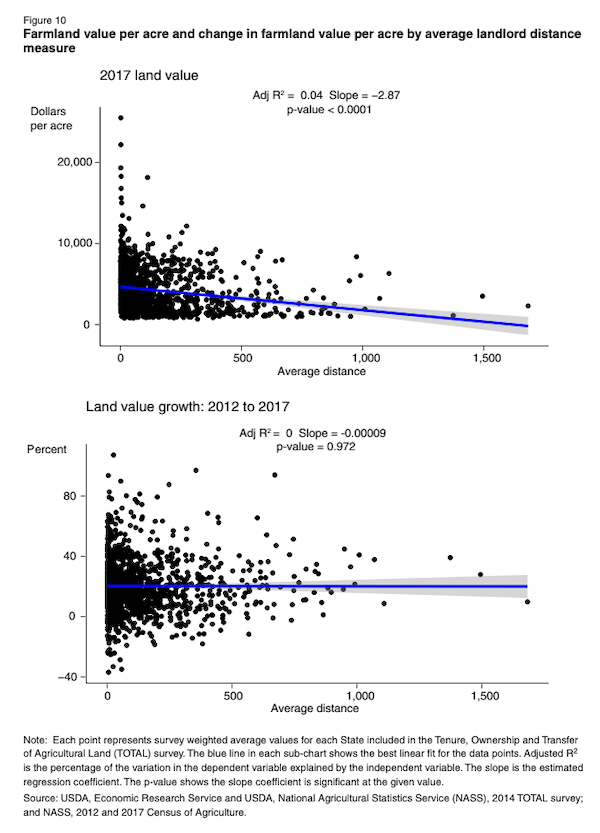

Impact on rental rates and farmland values: Analyzing farmland rental rates and land values between 2012 and 2017, the study shows that both measures tend to be associated with landlords who, on average, live farther from their lands, as well as a higher percentage of absent landlords. USDA notes that landlord absenteeism explains a larger portion of the variation in States’ farmland values in 2017 then in rental rates. Interestingly, the analysis finds no correlation between landlord distance with the growth in rental rates nor the growth in farmland values from 2012 and 2017, suggesting that absent landlords aren’t contributing to these changes.

USDA says several factors could explain the associations between these lower rents and land values with a higher rate of absenteeism. On the rent side, absent landlords less familiar with their own land’s productivity relative to other local operators may be more willing to accept lower rates, negatively influencing local values. USDA also proposes that local owners may be more willing to sell land that commands lower rental rates to nonlocal investors. Lower land values could be tied to absent landlords being less adept at maintaining their farmland relative to their local peers. It could also be related to nonlocal investors being more attracted to cheaper farmland.

Impact on soil health and conservation: There was no statistical association between the percentage of absent landlords and the percentage of acres utilizing conservation tillage or no-till farming practices in 2017. However, higher shares of absent landlords in a State are associated with a larger increase in acreage utilizing these practices as well as in the number of practices used from 2012 to 2017. Conversely, States with a higher percentage of absent landlords had a lower percentage of cropland with cover crop usage in 2017, but there was no statistical association between the percentage change in cover crop usage over the period studied. Previous literature analyzing conservation practices (at the county or more local levels) finds that farm operations with tenants were less likely to adopt conservation practices that provide benefits over the longer term. If this reflects the attitudes of operators renting land from absent landlords in general, then we might also expect them to be less likely to engage in conservation tillage practices.

Impact on the rural economy: At the State level, none of the absent landlord measures shows a statistically significant association with per capita income in 2017. However, they do show a negative association when using the growth in per capita income from 2012. The same findings are true at the county level. While it could be the case that absent landlords contribute to reduced growth or declines per capita income, it also could be the case that nonlocal investors prefer to buy land in areas with less vibrant economies because of lower financial barriers to entering economically depressed land markets. It could also be the case that agricultural landowners move away from economically depressed areas in search of better opportunities, but maintain ownership of farmland for various reasons, becoming landlords in the process.