Brazil continues to build out its infrastructure to accommodate the country’s massive grain trade with a particular focus on maximizing their share of China’s equally massive import market. The key to this plan is one that seems very simple on paper – more paved roadways connecting to the country’s northern ports. Turning that plan into reality has been a decades-long slog but there are clear signs that significant progress is finally being made with more on the way.

Brazil is somewhat famous for its poor highway system. Farmers and grain transporters routinely experience long and costly delays due to terrible conditions on unpaved and washed-out roadways. In April of 2019, for example, over 3,000 trucks transporting soybeans were stranded for weeks on an unpaved section of one of the country’s most important highways, BR-163. Grain traders ran up losses of as much as $400,000 a day as the highway department struggled to clear the vehicles.

BR-163 connects the main growing areas of central Brazil to what is known as the Northern Arc of ports along the Amazon River. The route is of fundamental importance for moving the flow of production out of Mato Grosso, the country’s biggest grain state, and other key Midwest growing regions. The Center-West region accounts for about half of Brazil’s soybean production.

That portion of BR-163 that caused so many headaches in 2019 has now been paved. The average round trip on the 1,000-mile final stretch of the highway from Sinop, in Mato Grosso, to Miritituba, in Pará state now takes 4 days compared to 10 previously. A recent report published by CONAB noted that exporting grain via this route to the Northern Arc ports is no longer considered just an alternative to Brazil’s southern ports. Rather, the BR-163 route has become key to accommodating central Brazil’s ever-expanding grain production.

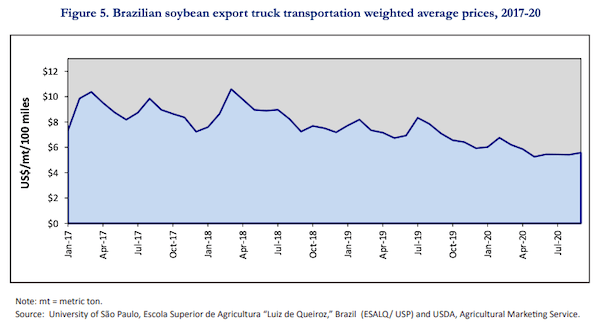

USDA reports that on the first 10 months of 2020, the cost of shipping a metric ton (mt) of soybeans 100 miles by truck decreased from $7.75 per mt to $5.48 per mt. This -29% drop was mostly due to the Brazilian real’s steep depreciation against the U.S. dollar. However, truck rates also declined because of the completion of the paving of BR-163 as the length of the trip shrank, along with the costs of fuel and truck maintenance. Truck rates in reais from Sorriso, in Mato Grosso to Rondonópolis (rail terminal) and to the northern river port of Miritituba decreased -3% and -15%, respectively, year over year.

The distance between the Mato Grosso-Pará border and key ports in the Santarém area, on the Amazon River, is about 600 miles. That compares to over 1,200 miles to the country’s busiest port, Port of Santos in the south. The largest port in the Northern Arc is Itaqui located in the northeast. This deepwater port can rely on an extensive rail network that connects to key production centers and is expected to eventually be capable of moving more than 17 million tons of grain a year when fully complete.

Brazil has plans to further expand roadway connections, too, as well as plans for a new rail line that will run parallel to BR-163 that could help to alleviate transportation congestion even more. Mato Grosso late last year announced a plan to auction more than 300 miles in road construction projects that will all connect to BR-163. The new railway route will transfer grain to ships at Miritituba, which lies 500 miles inland from the coast. Once moved along the river from Mirituba, onward shipment from northeastern Brazil will be around five days sailing time closer to the Panama Canal than the Port of Santos.

The rail project might be the one we really need to keep an eye on. Known as the Ferrogrão (EF-170) railroad, it has been met with a lot of pushback from indigenous Amazon tribes and their advocates but so far has continued to move forward. In fact, bidding for the project could begin in the first quarter of this year. The plan is to open the railway in 2030. The project is expected to cost upwards of $1.5 billion but a good chunk of that will likely come from outside investment. There is a lot of speculation that China will play a major role.

The reduction in the logistical costs provided by Ferrogrão will lead to grain production in Mato Grosso practically doubling in 10 years, according to projections by the Mato Grosso Institute of Agricultural Economics (Imea). The group sees production climbing from the 63.18 million tons registered in 2018 to 108 million tons in 2028, an increase of +71.1%. The area dedicated to grain production in the state is projected to go from 36.72 million acres to 55 million acres. (Sources: Proinde, USDA, US Soy, Bloomberg)