Agriculture’s war against weeds is not going great. For decades, herbicides like glyphosate were a farmer’s best friend, keeping fields weed-free and crop yields high. However, over time, some weeds developed genetic mutations that allowed them to survive even heavy herbicide applications. These survivors thrived, reproducing and spreading their resistant genes, creating a new generation of “superweeds.”

Across America’s farmlands, chemical-resistant weeds have proven to be formidable adversaries that continue to out-fox our most advanced herbicide science. The most notorious of these superweeds is Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri). The pigweed species has evolved into a behemoth, towering over crops and stealing vital resources like sunlight and water. Its thick, fibrous root system makes it extremely difficult to control even with mechanical methods and it’s now considered the most important weed problem in the southeastern and mid–south US.

Another persistent and widespread threat is waterhemp, which is now resistant to herbicides from at least seven herbicide modes of action. And some waterhemp populations are resistant to herbicides to which they have never been exposed. Farmers are also struggling to control kochia, which can produce as much as 30,000 seeds per plant and dent yields by some 70%. Kochia has become resistant to four groups of herbicides, including glyphosate.

The rise of chemical-resistant weeds has a cascading impact on US agriculture:

- Yield Losses: Weeds compete with crops for resources, leading to significant yield reductions. Estimates suggest that Palmer amaranth alone can cause yield losses of up to 70% in corn and soybeans.

- Increased Costs: Farmers are forced to resort to more expensive alternatives like multiple herbicide applications, specialized equipment, and labor-intensive hand weeding. This significantly increases the cost of production, squeezing profit margins and threatening farm viability.

- Environmental Concerns: Increased herbicide use can have adverse effects on soil health, water quality, and biodiversity. Moreover, the evolution of even more resistant weeds is inevitable, creating a potentially endless cycle of chemical escalation.

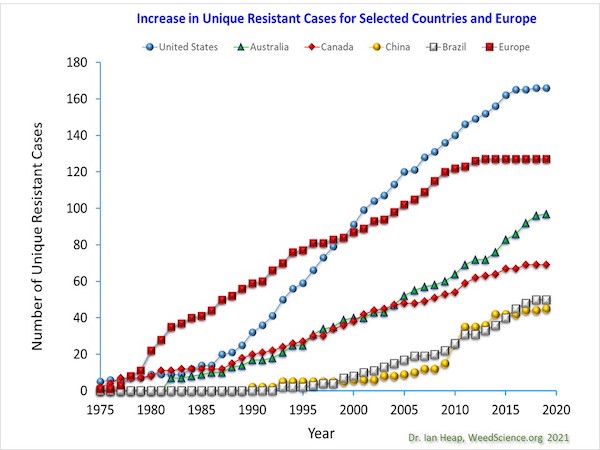

The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds, a database maintained by a group of scientists in over 80 countries, reduced effectiveness for glyphosate has been recorded in some 361 weeds. That includes 180 in the US, affecting corn, soy, sugar beets and other crops. At least 21 species globally have shown resistance to dicamba, which was only launched in the US in 2017.

Unfortunately for farmers, the toolbox for fighting these crop-killing weeds does not look like it will be expanding anytime soon, at least as far as new chemicals. Chemical producers Bayer, Corteva, and FMC have all warned that longer development and regulatory processes have constrained new products to combat weed resistance. Two decades ago, companies commercialized a product for every 50,000 candidates, but it now takes 100,000 to 150,000 attempts, Bob Reiter, head of research and development for Bayer’s crop science division said.

Farm chemical companies spent 6.2% of sales revenue on development of new active ingredients in 2020, down from 8.9% in 2000, AgbioInvestor said. Its data showed the introduction of new active ingredients fell by more than half in 2022 from 2000. (Sources: Reuters, Phys.org, Feedstuffs)

This is concerning to say the least. The only silver lining I see is companies like Carbon Robotics working to create weed killing solutions with lasers.