After wreaking havoc on global weather for over two years, the “La Niña” climate pattern finally ended in early March. We are now in the “neutral” phase of what’s called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle which should allow for more typical weather patterns through the US planting season. By late summer, neutral conditions are expected to give way to La Niña’s opposing climate pattern, “El Niño,” and some weather models predict it could be particularly extreme.

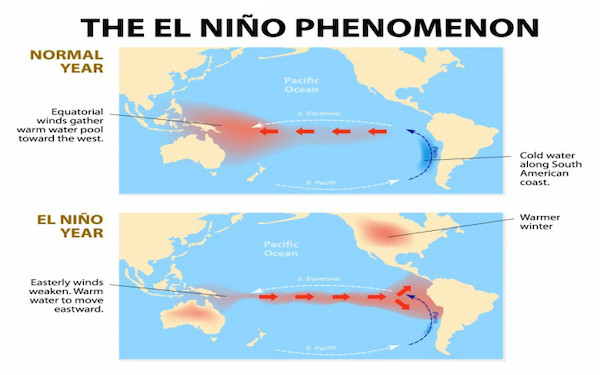

El Niño, meaning “boy child” in Spanish, is the “warm phase” of ENSO, marked by unusual warming of surface waters in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. The term was first used in the nineteenth century by fishermen in Peru and Ecuador to refer to the unusually warm waters that reduced their catch just before Christmas. El Niño events typically develop in the middle of the year and reach their peak during November–January, although this pattern can vary.

While the impacts of El Niño are never the same, strong and moderate events usually have a warming effect on average global temperatures. Typically, El Niño is associated with warm and dry conditions in southern and eastern inland areas of Australia, as well as Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and central Pacific islands. During the northern hemisphere summer season, the Indian monsoon rainfall generally tends to be less than normal. In the northern hemisphere winter, drier than normal conditions are typically observed over south-eastern Africa and northern Brazil.

During an El Niño pattern in the US, wetter than normal conditions are typically observed along the Gulf Coast and Southeast, which have in the past increased flooding. Northern areas of the US are typically dryer and warmer than usual, although the disruption to global atmospheric circulation can lead to unusually severe winter weather at higher latitudes, as well as longer and colder winters.

One of the strongest El Niño events on record occurred in 1982-1983. It is blamed for weather-related disasters on nearly every continent including droughts in Indonesia and Australia, widespread flooding across the southern United States, a lack of snow in the northern United States, and warmer winters across much of the mid-latitude regions of North America and Eurasia. In fact, the eastern United States experienced the warmest winter in roughly 25 years. Other side-effects, such as an uptick in mosquitoes, a loss in salmon off the coast of Alaska and Canada, and an increase in shark attacks off the western United States coast are all partially blamed on the event as well.

Remarkably, the trade winds during the 1982-1983 El Niño not only temporarily disappeared, they actually reversed. Some climate scientists believe the effects of this lingered and contributed to the intensity of the 1997-98 El Niño, which was also one of the most extreme on record.

The last extreme, or “super El Niño” event occurred in 2016 and is blamed for pushing global temperatures to the highest on record. The event was expected to cause severe drought in Australia’s wheat belt but the damage ended up being only minimal. In Argentina, soybean yields actually increase by nearly +10%. However, it reduced corn yields in South Africa by around -50% and dented palm oil yields in Malaysia by nearly -10%. Brazil had a particularly high number of forest fires during 2015, exacerbated by ongoing drought conditions in the Amazon region. However, northeastern Brazil witnessed excess rain. Central America experienced one of the worst droughts in history, leading to major crop losses.

Notably, during the winter of 2014–2015, the typical precipitation impacts of El Niño did not occur over North America. Ahead of the 2015–16 winter, it was hoped that El Niño would bring some relief from five years of drought in California but the event failed to end the long-term dryness. In the southeastern and south-central United States, above-normal rainfall occurred, with Missouri receiving three times its normal rainfall during November and December 2015. Major flooding also occurred along the Mississippi River.

According to Dr Mike McPhaden, a senior research scientist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), super El Niños typically occur about every 10 to 15 years. So while it would be unusual to have another extreme event so soon, it’s not impossible. “Nature has a way of tripping us up just when we think we know it all,” notes McPhaden.