The arrival of the combine during the middle of the 20th century had a dramatic impact on agriculture. The first self-propelled wheat combine was introduced in 1939, rising quickly to become the dominant way to harvest small grains in the US. By the 1960s, companies improved the technology to work for corn, and combine mechanisms for cotton, soybeans, and other crops followed. Below is a brief history of the combine and some of the ways it has transformed agriculture in the US.

Harvest Before the Combine

Before the 1800s, harvesting wheat was mostly done using hand tools. First they had to cut down the plants with a long-handled cutting tool such as a scythe. Next, they had to carry out threshing, which involved separating the edible grain from the inedible chaff by beating the cut stalks. Finally, they had to clean any remaining debris away from the seeds to make them suitable for use in a mill.

By the early 1800s, farmers in the US had adopted the use of mechanical headers and threshers. The header was pushed through the field by six horses from behind the machine, which reduced crop trampling. On the front edge of the header was a row of sharp teeth called sickles. Sliding back and forth, they touched the wheat stalk first and sliced it. To keep the wheat from falling on the ground, a reel circled around and paddles knocked the wheat into the header. The wheat then went up chute and fell down into a wagon, which was pulled by horses alongside the header. When the wagon was full, the header stopped, the wagon pulled out, another came in, and they started over.

The full wagons were transported to the thresher which was typically placed at a central harvest site to reduce travel time. Threshers were first run by horses walking in circles, and later by steam engines. Wheat was pitched inside the thresher, which separated the kernels from the head. The kernels then came back out of the machine in one spot, the straw and chaff came out another. So-called “sack-jigs” filled burlap sacks with grain, which they then passed to “sack sewers,” who literally sewed the sacks closed. Meanwhile, a “straw-buck” would place the straw into a wagon and haul it away. It took about 6 people to man a thresher, which also had to be constantly serviced. In total, a full wheat harvest crew was about 30 men and 30 horses.

The Rise of the Combine

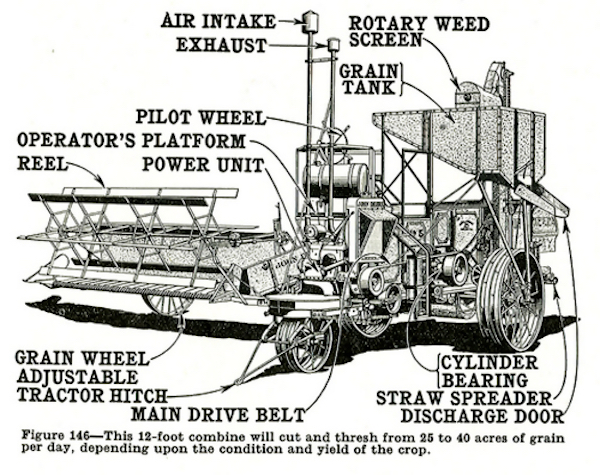

For many farmers, the introduction of the combine allowed them to exponentially increase production thanks to reduced labor costs and the ability to complete harvest before the weather changed. For those not familiar, “combine” is short for “combine harvester” and derives its name from the “combined” jobs that it performs – that of the header and thresher.

The first working combine was the invention of Hiram Moore and John Hascall of Kalamazoo County, Michigan, who tested it in the late 1830s, patenting it in 1836. Moore’s first combines required only about 6 to 10 men to run but even more horses or mules. It took 36 just to pull those early combine machines, which could weigh over fifteen tons. Still, the reduction in manpower was huge for farmers working with tight budgets. The combine also saved time by eliminating the need to transport the grain to the thresher. It was also faster thanks to the fact that it was pulled rather than pushed. The combine could harvest 40 acres a day instead of a couple hundred a season that the thresher could produce.

In the late 1880s, California farmer George Stockton Berry integrated the combine with a steam engine to provide power to the mechanics. Men forked straw from the rear of the separator back into the firebox to heat the water in the boiler. From 1911-1919, steam was slowly replaced with a gasoline engine, eliminating the need for wood or straw to heat the boilers and the manpower to feed it.

Then in 1915, a company called International Harvester from Chicago, Illinois, released its first line of tractor-pulled combines. This eliminated the need to house and feed dozens of animals. The tractor was also faster than horses, and obviously didn’t need breaks. J.I. Case and John Deere both introduced their tractor-pulled combines in the 1920s.

In 1939, a company called Massey Harris (now Massey Ferguson) went a step further and created the first self-propelled combine. The Massey Harris Model 21 meant one less machine to keep gassed up. They were also smaller than the horse-pulled variety, and were substantially cheaper. The Massey Harris combine also included a grain tank that could hold about 100 bushels of wheat, which could be dumped all at once into the back of a truck bed with the unloading auger. Additionally, the Massey Harris combine introduced a closable cab to help protect farmers from the dust and heat.

The No. 21 is well known for its role in the famous “Harvest Brigade,” Carroll’s innovative idea created during WWII. Massey-Harris convinced the War Production Board (WPB) that if it were permitted to build 500 extra machines over its allotment, they could harvest at least 15 million bushels of grain from more than 1 million acres while releasing some 1,000 tractors for other work and saving 500,000 gallons of fuel. Basically, the 500 machines would only be sold to farmers who signed a document guaranteeing that they would harvest at least 2,000 acres with their new combine.

The majority of today’s combines are rotary combines offering multi-crop threshing and rotary separation. Other common equipment includes GPS, data collection, panoramic view cabs, touchscreen monitors, and more. Typical new models are able to harvest almost 100 tons of small grains per hour. The USDA reported in the 2017 survey of equipment on farms that there are currently 323,347 combines on farms in the US. A total of 6,272 new combine harvesters were sold in 2021 alone.